Direct Estimates

Contents

2. Direct Estimates#

To fully benefit from the Guidelines, it is necessary first to understand the background materials, including a description of the design-based setting, followed by typical direct estimators, along with the advantages and disadvantages of their applications. The goal of Chapter 2: Direct Estimates is to present background material for the chapters that follow. The chapter begins by describing the design-based setting. Then it gives a description of the typical direct estimators and their advantages and disadvantages in their applications. Finally, some tips to evaluate estimates are provided.

Direct estimates are generated by taking a sample from the target universe of observations, surveying that sample, then using statistical techniques to generalize the results to the entire population of interest. Sample surveys provide reliable estimates of a target population without observing the entire population. Sample survey data is used to produce direct estimates of totals, means, and other characteristics for the whole population and other domains. Here, “direct” means that only the sample units from the area are used (See Lohr [2010] or Cochran [2007] for a thorough treatment of sampling theory and direct estimation).

In areas with a sufficiently large sample size, statistical institutes often report direct estimates by default due to their desirable properties with respect to the sampling design (Molina [2019]). Though there are some global norms, defining “sufficiently large,” usually measured by the coefficient of variation, is done by the data producers. In cases where direct estimates are not sufficiently large, the results may still be reported, but the lack of quality is usually flagged for users. In instances where the desired quality is not met, small area estimates are necessary. Hence, small area estimates may be judged by how much they improve the quality of the direct estimates.

2.1. Design-Based Estimation#

The traditional way to provide estimates of finite population parameters based on survey data is to rely on design-based (or repeated sampling) estimation methods. However, using a survey to produce direct estimates of adequate precision for particular domains of the population can be economically prohibitive since it may require considerably large sample sizes (Cochran [2007]). Even in the case of limitless resources, huge samples may not be advisable because of a heightened risk of non-sampling or implementation error. The quality of direct design-based estimates is evaluated with respect to their sampling design, that is, with respect to all the possible samples taken from the population under the proposed sampling design (Molina [2019]). In this scenario, the values of the variable of interest are considered fixed and they only vary due to the variation induced by the sampling design (ibid).1

Consider the following notation for the next sections:

\(U\) is the target population, e.g. the set of inhabitants in a country, of size \(N\).

\(y_{1},\ldots,y_{N}\) are measurements of the study variable at the population units (assumed to be fixed).

Target finite population parameter or quantity of interest: \(\delta=h(y_{1},\ldots,y_{N})\). For example, the population mean \(\bar{Y}=\) \(\frac{1}{N}\)\(\sum_{j=1}^{N}\)\(y_{j}\).

\(s\) is a random sample of size \(n\) drawn from the population \(U\) according to a given survey design.

\(r=U-s\) is the set of non-sampled units (size \(N-n\)).

There are \(D\) subpopulations/domains/areas, indexed by \(d=1,\ldots,D\), of sizes \(N_{1},\ldots,N_{D}\).

The mean of a variable \(Y\) in a subpopulation/domain/area \(d\) is given by \(\bar{Y}_{d}=N_{d}^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^{N_{d}}y_{di}\), where \(y_{di}\) denotes the value of \(Y\) for individual \(i\) in area/domain \(d\).

\(s_{d}\) is the subsample of size \(n_{d}\) (which may be the empty set) from domain/area \(d\), where \(\sum_{d=1}^{D}n_{d}=n\).

\(r_{d}\) is the set of elements outside the sample of area \(d=1,\ldots,D\).

\(\pi_{di}\) is the inclusion probability of individual \(i\) in the sample from area/domain \(d\).

\(\omega_{di}=\pi_{di}^{-1}\) is the sampling weight of individual \(i\) in area/domain \(d\).

\(\pi_{d,ij}\) is the joint inclusion probability of individuals \(i\) and \(j\) in the sample from area/domain \(d\).

With this notation in mind, the following subsection presents the standard direct estimators, including basic direct estimators such as Horvitz-Thompson (HT), Hájek, and estimators requiring auxiliary data like GREG and calibration estimators.

2.1.1. Basic Direct Estimators#

Horvitz-Thompson (HT)

The Horvitz-Thompson (HT) estimator of the total of area/domain \(d\), \(Y_{d}=\sum_{i=1}^{N_{d}}y_{di}\), is \(\hat{Y}_{d}=\sum_{i\in s_{d}}\omega_{di}y_{di}\). This estimator is unbiased under the sampling design.

To estimate the mean of area/domain \(d\), \(\bar{Y}_{d}=N_{d}^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^{N_{d}}y_{di}\), the HT estimator is \(\hat{\bar{Y}}_{d}=N_{d}^{-1}\sum_{i\in s_{d}}\omega_{di}y_{di}\). Note that here it is assumed that the true area’s population \(N_{d}\), is known.

Assuming positive inclusion probabilities \(\pi_{di}\) and \(\pi_{d,ij}\) for every pair of units \(i,j\) in the area, an unbiased estimate of the variance is given by:

One typical challenge in applications is that there is not enough information about the sampling design. Without the second-order inclusion probabilities \(\pi_{d,ij}\), the formula above cannot be applied. Nevertheless, for certain sampling designs, where \(\pi_{dij}\approx\pi_{di}\pi_{dj}\), for \(j\neq i\), the second term of the formula approximates zero. Therefore, a simpler variance estimator, which does not depend on the second-order inclusion probabilities \(\pi_{d,ij}\), would be: \(\widehat{\mathrm{var}}_{\pi}(\hat{\bar{Y}}_{d})=N_{d}^{-2}\sum_{i\in s_{d}}\omega_{di}(w_{di}-1)y_{di}^{2}\), where \(\omega_{di}=\pi_{di}^{-1}\) is the sampling weight of unit \(i\) in area/domain \(d\).

Hájek

Despite the HT estimator being unbiased under the sampling design, its variance under the design may be quite large. An alternative, although slightly biased, is Hájek’s estimator. This estimator is obtained just by using the sampling weights for the considered area to estimate \(N_{d}\); consequently, for estimation of \(\bar{Y}_{d}\), it does not require knowing the population size of area \(d\). The Hájek estimator uses \(\hat{N}_{d}=\sum_{i\in s_{d}}\omega_{di}\) instead of \(N_{d}\) to estimate the area mean \(\bar{Y}_{d}\). However, an unbiased estimator of its variance is obtained by replacing \(y_{di}\) by \(e_{di}=y_{di}-\hat{\bar{Y_{d}}}^{HA}\) in the variance estimator of the HT estimator.

Both HT and Hájek use only area-specific sample data, that is to say, they only use the portion of the survey data for a given area \(d\).

Variance Estimation in Applications

Another challenge that may be encountered in applications is that, in many domains/areas \(d\), there is only a single primary sampling unit (PSU) present in the survey data; hence, the habitual variance estimator cannot be calculated and some approximation of the variance is required.

Alternatives to approximate the variance of the estimator that depend on the sampling design and the information available to the practitioner include linearization, a balanced repeated replication BRR method with Fay’s method,2 as well as jackknife and bootstrap techniques. Rao [1988] and Rust and Rao [1996] provide a deeper discussion on variance estimation in sample surveys and application examples. Additionally, Bruch et al. [2011] provide an overview of variance estimation in the presence of complex survey designs.

2.1.2. GREG and Calibration Estimators#

Unlike the basic direct estimators presented above, the Generalized Regression (GREG) and, more generally, calibration estimators, require auxiliary information, such as the population totals or means of auxiliary variables in \(d\), \(\bar{X}_{d}=N_{d}^{-1}\sum_{i=1}^{N_{d}}y_{di}\). If \(\hat{\bar{X}}_{d}\) is the HT estimator of \(\bar{X}_{d}\), then the GREG estimator of \(\bar{Y}_{d}\) is given by: \(\hat{\bar{Y}}_{d}+(\hat{\bar{X}}_{d}-\bar{X}_{d},)'\hat{\bar{\boldsymbol{B}}}_{d}\), where \(\hat{\bar{\boldsymbol{B}}}_{d}\) is the weighted least squares estimator of the coefficient vector \(\boldsymbol{\beta}_{d}\) in linear regression of \(y_{di}\) in terms of the vector \(x_{di}\) in area \(d\). For an exhaustive presentation of GREG estimators, see Rao and Molina [2015].

2.1.3. Pros and Cons of Direct Estimators#

Data requirements:

Sampling weights \(\omega_{di}\) for survey units.

True population size \(N_{d}\) of area \(d\) for HT estimator of \(\bar{Y}_{d}\).

Some advantages and disadvantages of direct estimates are the following:

Pros:

They make no model assumptions (non-parametric).

HT is exactly unbiased under the sampling design for large areas. Hájek and GREG estimators are approximately unbiased under the sampling design for large areas.

It is an unbiased estimator under the sampling design if the expected value (mean) of the estimator across all the possible samples \(s_{d}\) drawn from area \(d\) with the given design is equal to the population parameter. In other words, if its design bias is equal to zero for all the values of the parameter. The estimator \(\hat{\theta}_{d}\) of parameter \(\theta\) is unbiased if and only if \(E_{\pi}(\hat{\theta}_{d})-\theta_{d}=0\).

Consistency: as the sample size increases, the probability that the estimator \(\hat{\theta}\) differs from the true value \(\theta\) by more than \(\varepsilon\) approximates 0, for every \(\varepsilon>0\).

Additivity (Benchmarking property): \(\sum_{d=1}^{D}\hat{Y}_{d}=\hat{Y}\), that is, the direct estimate of the total for a larger area covering several areas coincides with the aggregation of the estimates of the totals for the areas within the larger area.

Cons:

Inefficient for small areas. For an area \(d\) with small \(n_{d}\), traditional area-specific direct estimators do not provide adequate precision.

Direct estimates cannot be calculated for non-sampled domains.

2.1.4. Example: Direct Estimates of Poverty Indicators#

Example based on Molina and Rao [2010] and Molina [2019].

Target population: \(N\) households in a country.

There are \(C\) different areas/clusters \(c=1,\ldots,C\) of sizes \(N_{1},\ldots,N_{C}\) respectively.

Let \(y_{ch}\) be total income for each household \(h=1,\ldots,N_{c}\) in area/cluster \(c=1,\ldots,C\).

Let \(z\) be a fixed poverty line.

FGT indicators are defined as \(F_{\alpha ch}\)=\(\left(\frac{z-y_{ch}}{z}\right)^{\alpha}I(y_{ch}<z),\:h=1,\ldots,N_{c},\:\alpha=0,1,2,\) where the indicator function \(I(\cdot)\) is \(1\) if household \(h\) is under the poverty line \(z\), and \(0\) otherwise (Foster et al. [1984]).

Then, for every cluster/area \(c\), the FGT poverty indicator of order \(\alpha\) for area \(c\) is \(F_{\alpha c}\)= \(\frac{1}{N_{c}}\)\(\sum_{h=1}^{N_{c}}\)\(F_{\alpha ch}\).

The goal is to estimate the poverty indicator \(F_{\alpha c}\) for every cluster/area \(c\); take a random sample \(s_{c}\) of size \(n_{c}\) (which might be equal to zero) from cluster/area \(c\).

Horvitz-Thompson estimator: \(\hat{F}_{\alpha c}=\frac{1}{N_{c}}\sum_{h\in s_{c}}\omega_{ch}F_{\alpha ch}\).

Hájek estimator: \(\hat{F}_{\alpha c}=\frac{1}{\hat{N}_{c}}\sum_{h\in s_{c}}\omega_{ch}F_{\alpha ch}\), where \(\hat{N}_{c}=\sum_{h\in s_{c}}\omega_{ch}\).

Here, \(\omega_{ch}=\pi_{ch}^{-1}\), where \(\pi_{ch}\) is the inclusion probability of household \(h\) in the sample of cluster/area \(c\).

2.2. Evaluation of Estimates#

Comparison of estimates is based on statistical measures of precision and accuracy. It is stated that estimate \(\hat{\theta}\) has more precision than estimate \(\hat{\theta}'\) if the (replicable) values of the estimate \(\hat{\theta}\) are closer to each other than the ones of \(\hat{\theta'}\), that is to say, if the realizations of \(\hat{\theta}\) have less dispersion. On the other hand, accuracy measures the closeness of estimate \(\hat{\theta}\), i.e. \(E(\hat{\theta})\), to the true value of the population parameter \(\theta\).

For example, the estimated mean squared error (MSE) is a measure of precision (measured by the variance of the estimate \(\hat{\theta}\)) and accuracy (measured by the square bias of the estimate \(\hat{\theta}\)).

The particular error measures and “acceptable” error levels depend on National Statistical Office’s guidelines or practitioners/researchers. The most common error measures of an estimator are: standard error, variance, coefficient of variation (CV), and the mean squared error (MSE). The smaller the value for all these measures, the better is the estimator.

The sections above reviewed direct estimators for means and totals. Direct estimators are obtained similarly for any other target parameter that is additive in the individual observations. Direct estimators are recommended at the national level and for disaggregated levels where direct estimators have a coefficient of variation (CV) below an established threshold for every area Molina [2019]. For disaggregations where direct estimators have a CV above the CV threshold or absolute relative bias (ARB) above a given ARB threshold, direct estimates are not recommended (see Chapter 3: Area-level Models for Small Area Estimation and Chapter 4: Unit-level Models for Small Area Estimation for the application of indirect estimators). If there are areas where not even the indirect estimators satisfy the former requirements, it is recommended to properly highlight these estimates, indicating that these have low quality.3

In order to obtain a clear assessment of the precision and accuracy gains of model-based SAE methods over direct estimation, it is helpful to present the following information when reporting poverty estimates:4

Area code \(d\)

True population size of area \(d\), \(N_{d}\)

Sample size of area \(d\), \(n_{d}\)

Direct estimate of poverty for area \(d\), \(\hat{F}_{\alpha d}\)

Small area estimate of poverty for area \(d\), for example, EB \(\hat{F}_{\alpha d}^{EB}\)

Estimated variance of area \(d\), \(\hat{F}_{\alpha d}\)

Estimated mean squared error (MSE) of \(\hat{F}_{\alpha d}^{EB}\) in area \(d\) or

Coefficient of variation (CV) of both \(\hat{F}_{\alpha d}\) and \(\hat{F}_{\alpha d}^{EB}\) in area \(d\)

Direct estimators have the advantage that they are (approximately) unbiased under the sampling design. When comparing two unbiased estimators, choosing the one with the smallest variance is recommended.5 If one of them is not unbiased, it is recommended to select the one with the smallest MSE (Molina and García-Portugues [2021]), as it is preferable to tolerate small amounts of bias if there are large gains in precision (the bias-variance tradeoff). The model-based SAE methods presented in the subsequent chapters introduce some bias under the design while decreasing the MSE. There is, however, a limit to the amount of bias that can be tolerated before the estimators lose utility.

Why use the coefficient of variation (CV)? The CV of \(\hat{\theta}\), \(cv(\hat{\theta})=\sqrt{\mathrm{var}(\hat{\theta})}/\theta\), is a relative measure of error, which makes it unitless and easier to interpret than the MSE. Nevertheless, for the CV to have a correct interpretation, the value of the estimate must be greater than zero. Moreover, when estimating a proportion \(P\) (poverty rates, for example), larger sample sizes are often necessary to keep the error measure below a certain limit than the sample size required when estimating totals (Molina [2019]).6 Since the CV increases as the proportion \(P\) decreases, the CV is no longer a measure of the relative error but a measure of how small the proportion \(P\) is. Therefore, calculating the MSE (or its root) for proportions \(P\) is a better option.

2.2.1. Example: Bias vs MSE#

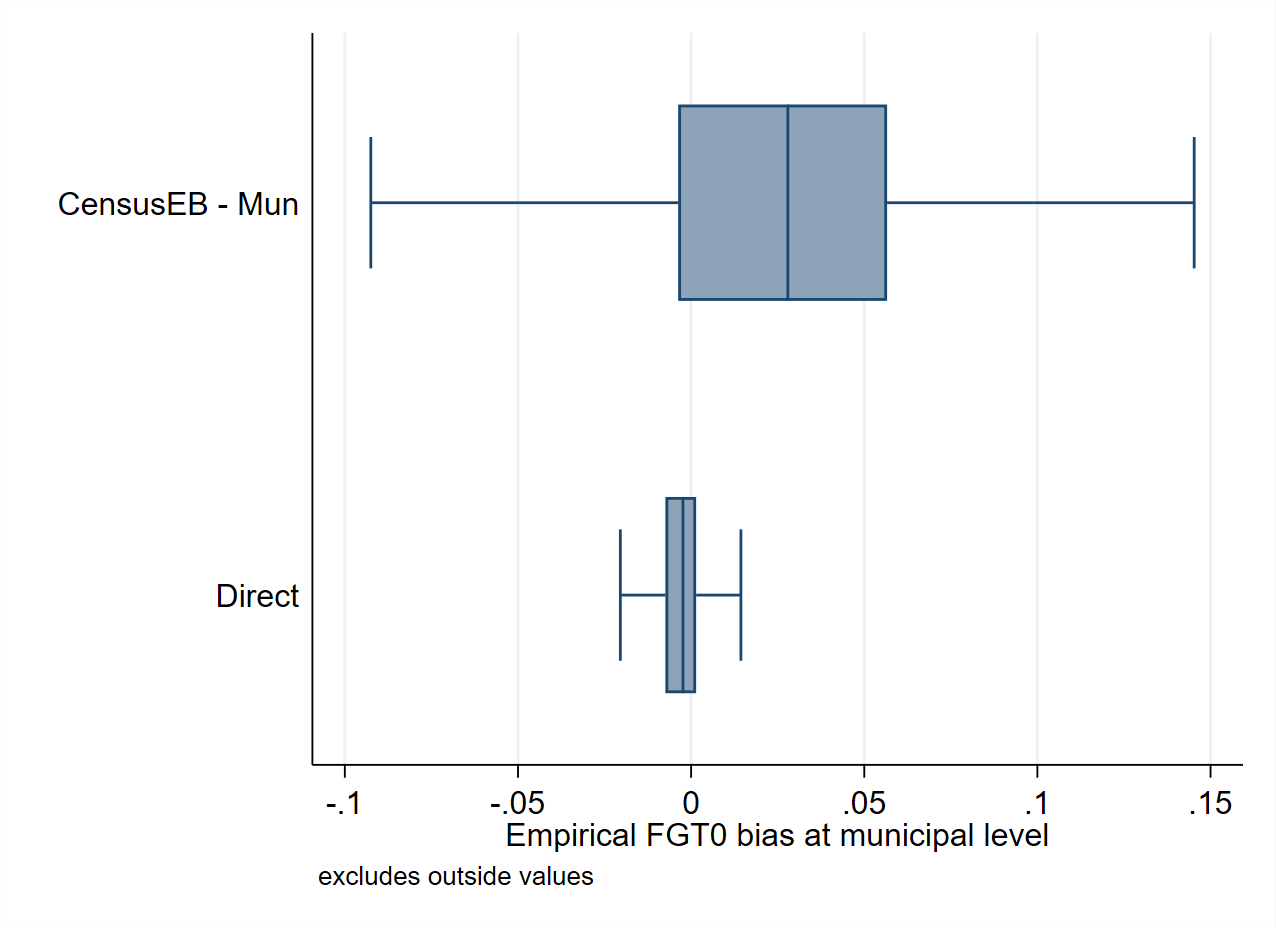

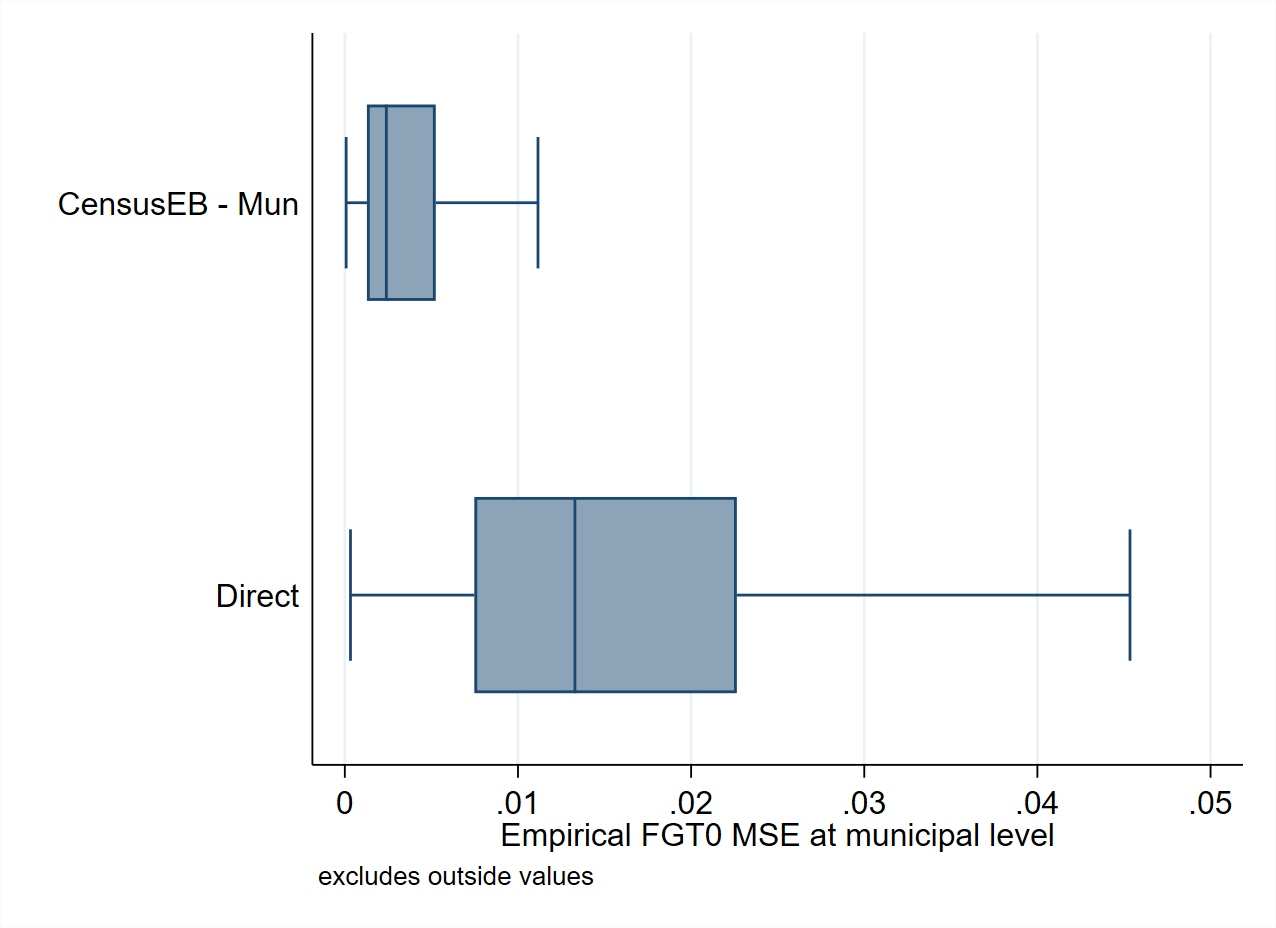

Fig. 2.1 shows the design bias (left) and design MSE (right) of direct estimates of FGT0 indicators (poverty rates) compared to unit-level model-based estimators, both presented at the municipal level. It is essential to notice that even though the direct estimate’s bias is approximately equal to 0, its variance (or MSE) in many areas is much greater than the one from the model-based estimators.

Fig. 2.1 Bias and MSE of direct estimates of the FGT0 indicators at the municipal level#

Source: Based on 500 samples drawn from the Mexican Intercensal survey which is used as a census of 3.9 million households (see Corral et al. [2021]). Figure shows the comparison between design bias, where Hájek direct estimates are approximately unbiased, but have a large MSE. On the other hand, indirect methods such as unit-level SAE, Census EB, sacrifice design bias in pursuit of improved precision.

2.3. Appendix#

2.3.1. Definitions#

Definitions are based on Rao and Molina [2015] and Cochran [2007].

Unit of analysis: the level at which a measurement is taken. For example, persons, households, farms, and firms.

Target population or universe: The population of interest from which the relevant information is desired. For example, the country’s population in the case where national living standards are the objective.

Domain/area: domain \(d\) may be defined by geographic areas (state, county, school district, health service area) or socio-demographic groups or both (a specific age-sex-race group within a large geographic area) or other subpopulations (e.g., set of firms belonging to a census division by industry group).

Finite population parameter \(\theta\): quantity computed from the \(N\) measurements in the units of analysis in the population. It is often a descriptive measure of a population, such as the mean, variance, rate, or proportion.

Estimator \(\hat{\theta}\): function of the sample data that takes values “close” to \(\theta\).

Direct estimator \(\hat{\theta}_{d}\) of \(\theta_{d}\): estimator based only on the domain-specific sample data. An estimator of an indicator for area \(d\), \(\theta_{d}\), is direct if it is calculated only using data from that domain/area \(d\), without using data from any other area. These estimators have the advantage of being (at least approximately) unbiased but tend to have low precision in areas with small sample size.

Unbiased estimator under the sampling design: If the estimator’s expected value (mean) across all the possible samples is equal to the population parameter. If its design bias is equal to zero for all the values of the parameter. The estimator \(\hat{\theta}\) of parameter \(\theta\) is design-unbiased if and only if \(E_{\pi}(\hat{\theta})-\theta=0\).

Estimation error: \(\hat{\theta}-\theta\), note that the estimation error for a given sample is typically different from zero even if the estimator is unbiased. The design bias is the mean estimation error across all the possible samples: \(Bias_{\pi}(\hat{\theta})=E_{\pi}(\hat{\theta})-\theta=E_{\pi}(\hat{\theta}-\theta)\).

Mean squared (estimation) error (MSE): \(MSE(\hat{\theta})=E[(\hat{\theta}-\theta)^{2}]\), note that \(MSE(\hat{\theta})=Bias_{\pi}^{2}(\hat{\theta})+Var_{\pi}(\hat{\theta})\) in the design-based setup, where \(\theta\) is not random. In the model-based setup, it is \(MSE(\hat{\theta})=Bias^{2}(\hat{\theta})+Var(\hat{\theta}-\theta)\).

Standard error (SE) of \(\hat{\theta}\): is the standard deviation of the sampling distribution of the estimator \(\hat{\theta}\) of parameter \(\theta\).

Coefficient of variation (CV) of \(\hat{\theta}\): \(cv(\hat{\theta})=\sqrt{var(\hat{\theta})}/E(\hat{\theta})\) is the associated standard error of the estimate over the expected value of the estimate (\(E(\hat{\theta})=\theta\) when the estimator is unbiased. The CV is also known as the relative standard deviation (RSD).

Absolute Relative Bias (ARB) of \(\hat{\theta}\): \(ARB(\hat{\theta})=|(E(\hat{\theta})-\theta)/E(\hat{\theta})|\).

Consistency of \(\hat{\theta}\): as the sample size increases, the probability that the estimator \(\hat{\theta}\) differs from the true value \(\theta\) in more than \(\varepsilon\) approximates 0, for every \(\varepsilon>0\).

Simple random sampling (SRS): Sampling approach where a sample is chosen from a larger population at random. First-order inclusion probabilities are equal across elements ().

With replacement: Elements within the population may be randomly sampled multiple times. In an ordered design sample containing information on the drawing order and the number of times an element is drawn, every ordered sample has the same selection probability (ibid).

Without replacement: Elements are selected from a population without replacement. Every sample of a fixed size has an equal probability of being selected (ibid).

Sampling proportional to size: Method of sampling from a finite population where size measures for each unit are available. The probability of selecting a unit is proportional to its size. It is often used for multistage sampling (Skinner ).

Informative sampling: If the sample selection probabilities are related to the outcome values (Rao and Molina [2015]). This results in a set of base weights reflecting the unequal probability of being sampled. Under informative sampling, in the absence of weights, the values of the outcome variable are not representative of the population ().

Benchmarking: A practice where the direct estimator is assumed to be reliable and adjustments to the small area estimates are necessary to ensure agreement with the reliable estimator (Rao and Molina [2015]). For example, the direct estimator could be the national level poverty rate and small area estimates for the areas within the country are adjusted to ensure agreement between the aggregate national poverty rate and the direct estimate of national poverty.

2.4. References#

- BMunnichZ11

Christian Bruch, Ralf Münnich, and Stefan Zins. Variance estimation for complex surveys. Deliverable D3, 2011.

- Coc07(1,2,3)

William G Cochran. Sampling techniques. John Wiley & Sons, 2007.

- CHMM21

Paul Corral, Kristen Himelein, Kevin McGee, and Isabel Molina. A map of the poor or a poor map? Mathematics, 2021. URL: https://www.mdpi.com/2227-7390/9/21/2780, doi:10.3390/math9212780.

- FGT84

James Foster, Joel Greer, and Erik Thorbecke. A class of decomposable poverty measures. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 52:761–766, 1984.

- Loh10

Sharon L Lohr. Sampling: design and analysis (advanced series). Cengage Learning, 2nd edition, 2010. ISBN 0495105279. URL: http://dni.dali.dartmouth.edu/8vxeqmju4q43/12-bailee-klein-1/read-0495105279-sampling-design-and-analysis-advanced-series.pdf.

- Mol19(1,2,3,4,5)

Isabel Molina. Desagregación De Datos En Encuestas De Hogares: Metodologías De Estimación En áreas Pequeñas. CEPAL, 2019. URL: https://repositorio.cepal.org/handle/11362/44214.

- MGarciaP21

Isabel Molina and Eduardo García-Portugues. A First Course on Statistical Inference. Bookdown.org, 2021. Accessed: 2010-06-22. URL: https://bookdown.org/egarpor/inference/.

- MR10(1,2)

Isabel Molina and JNK Rao. Small area estimation of poverty indicators. Canadian Journal of Statistics, 38(3):369–385, 2010.

- Rao88

JNK Rao. Variance estimation in sample surveys, chapter 17, pages 427–447. Volume 6. Elsevier B.V, 1988. URL: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-7161(88)06019-5.

- RM15(1,2,3,4,5)

JNK Rao and Isabel Molina. Small Area Estimation. John Wiley & Sons, 2nd edition, 2015.

- RR96

Keith F Rust and JNK Rao. Variance estimation for complex surveys using replication techniques. Statistical methods in medical research, 5(3):283–310, 1996.

2.5. Notes#

- 1

Rao and Molina [2015] note that, it is possible to model population values as random instead of fixed to obtain model-dependent direct estimates. For such estimates, their inferences are based on the probability distribution induced by the model; and will typically not depend on survey weights.

- 2

Section 4 of details the application of the method at the U.S. Census Bureau.

- 3

The CV threshold can vary from scenario to scenario; some practitioners and national statistical offices consider that estimates with a CV above 20% are not reliable.

- 4

See Molina and Rao [2010] for a clear example of poverty indicators report and assessment.

- 5

Since \(MSE_{\pi}(\hat{F}_{\alpha d})=Bias_{\pi}^{2}(\hat{F}_{\alpha d})+Var_{\pi}(\hat{F}_{\alpha d})\) and direct estimators are (approximately) unbiased, both MSE and variance are approximately equal. This holds for areas with large sample size \(n_{d}\), for areas with small sample size, the Hájek estimator is biased.

- 6

The CV will tend to be large when the poverty rate for a given area is low since even a small variance will yield a relatively large CV. The only way to remedy such a result is by increasing the sample size.